Building community through electronic music: a conversation with Mark Fell and Rian Treanor

Rotherham-based father and son Mark Fell and Rian Treanor are renowned musicians and artists responsible for a vast catalogue of sound art projects and installations worldwide. Their musical output spans Mark’s influential albums as half of SND in the late 90s and collaborations with the likes of DJ Sprinkles, Errorsmith and Will Guthrie, to Rian’s records for the Death of Rave and Planet Mu labels, which refract footwork and UK bass music through an experimental lens.

In recent years, the pair have turned their focus to grassroots projects in and around their home town, including Rian’s Electronic Music Club, a monthly after-school workshop that has seen the likes of RP Boo and Bianca Scout teach teenagers about music-making and DJing. Signal Sounds has donated a bunch of hardware synths to the project, and an incredible album featuring some of these collaborations was released last month. Rian has also created a suite of accessible online music tools on the site for people to make music anywhere.

The Electronic Music Club pop-up at Hope Works, Sheffield, in January 2025

The Electronic Music Club pop-up at Hope Works, Sheffield, in January 2025As part of this year’s No Bounds festival in Sheffield and the surrounding area, Mark and Rian are curating a day of performances and workshops at Rotherham’s Hope Centre on Sunday 12 October, and Signal Sounds will be making the drive south to host a room full of synths for people to try. If you’re interested in modular synths or just want to have a go on a keyboard or drum machine, Luke and Tom will be on hand to answer questions and give you a helping hand.

Ahead of the event, Tom caught up with Mark and Rian for a chat about their passion for community work, the power of music for young people, and to find out why Mark thinks synths should be prescribed on the NHS.

Mark Fell and Rian Treanor (Photo credit: RP Boo)

Mark Fell and Rian Treanor (Photo credit: RP Boo)Tom: You’re very passionate about working in your home town. For people who don’t know it, what’s Rotherham like?

Mark: Rotherham has a lot of socioeconomic problems. It has a very diverse population with lots of different ethnic groups. It’s always being brought into national debates whenever there's talk about issues to do with migration and cohesion and stuff like that. It’s used in a way to assert certain positions that we don't agree with. We live in a very diverse community, and we like that, and we're part of that. So our agenda is to do work in the town but also change perceptions about the town and the way it's hijacked and used in these conversations about the failure of multiculturalism or whatever.

Tom: So tell me a bit about where you are now and how you got here, in terms of community-based music projects.

Rian: We've been developing a lot of ideas around group music-making for the last five to seven years. But then since Covid it's become a really central thing.

Mark: Before Covid we were traveling like crazy, doing shows all over the place and having a good time, but when Covid came around, that all stopped and we were just stuck here. At that point we started to look at how we could do projects that weren’t just streaming shows from our studios or whatever.

We did this project called Intersymmetric which is a kind of 808-style drum grid interface, but it's synchronised. 3So if you log on to it, if I make a change then you'll see the change. I think it was the first multi-user drum machine that was synchronised over the internet. Off the back of that, once lockdown subsided and we started doing stuff again, I think that experience made us more aware of the value of group interaction and getting people involved. It feels like a catastrophic global moment where we have a climate crisis, we have wars going on everywhere, so it's like what can we do? Now it seems to me the best thing we can do to make a positive difference is to work with the kids in the town. These kids deserve it.

Rian: And we didn't just come to this point through doing Intersymmetric. We've been doing things for some years before. Before Covid happened I was already thinking I didn’t want to do loads of touring gigs, I wanted to focus on doing workshops and working with people, because I find it a lot more meaningful. You're engaging together in something. It's not just someone being on a stage as a top-down sort of thing. With the online music stuff too, the key thing is connecting people. There are so many unknowns that are exciting to explore so we've just been kind of doing a lot of that since.

Mark: We did one project in Braga in the north of Portugal in 2021 with an organisation called GNRation. The director had seen the drum machine thing and he commissioned us to work with CERCI, which is a service for young adults with additional needs. We couldn't go there in person, but over about three months we did one or two workshops a week. Because Rian was living here as well, rather than plan the whole thing in advance, we just planned the next workshop as soon as we’d done each one. It was this process of seeing what we can do, learning things, then implementing it for the next workshop a few days later. And with this group we did really amazing things. We ended up getting them to do physically embodied Markov chains where they'd have ropes in the room pulling them…

Rian: We did a lot of things like exploring musical group systems but we did it in a way that's embodying it. We tried to do some things digitally and it was very difficult to follow. So it was like, what can we do? Right, everybody stand in a line and hold this rope. When it goes over your head, make a noise. When it goes under, you make a different noise. So then you start getting into quite complicated conditional sort of pattern-generating stuff.

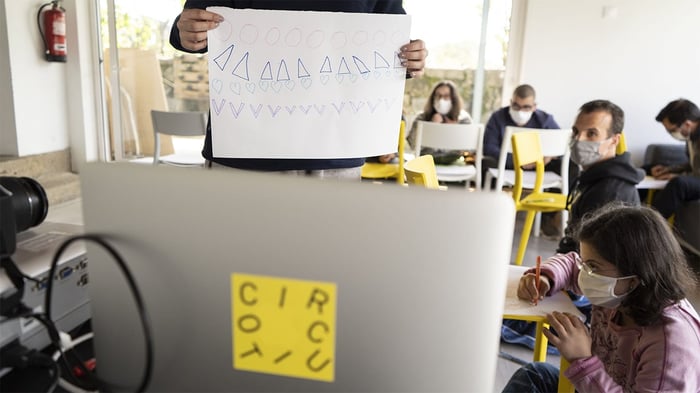

The CERCI workshop in Braga, Portugal, in 2021

The CERCI workshop in Braga, Portugal, in 2021We did another thing where you stand in a circle. You've got a piece of rope and you're going to give the end of the rope to the person next to you. So then that goes around and you create a circle with a piece of rope. Now if you feel the rope tugging in your right hand, you make a sound and then you tug the rope in your left hand. So then you can pass around a sort of sequence, but then you can make more complicated patterns. We got them to a point where they had choices. You could either send it to player one or player two. And they were actually embodying this Markov chain process. The tutors were astonished because it's really hard to get these groups to have these meaningful coordinated relationships in group activities. We just came across this thing that was amazing.

Mark: The crucial thing was that we realized that it wasn't as though the group were interacting with the music or the systems. The group were interacting with each other using the system and the structures as a kind of mediating thing, and the essential thing was about facilitating group dynamics. The leader of the service said that particular group struggled to have cohesive group behaviors because of their disabilities.

So basically that became a kind of really interesting sort of key position: that when we're working with technology and music, we're not necessarily just interacting with technology and music, we're interacting with each other. So music is a kind of a way of constructing social bonds - which of course it is… do you know what I mean? So that's what we brought to the Electronic Music Club.

Finlay Shakespeare with participants at the Electronic Music Club

Finlay Shakespeare with participants at the Electronic Music ClubWhile we were doing this, I was also involved in the local music hub. Each town in England has a music hub that coordinates music education in the town with the schools.I was one of the trustees on this service and it became clear to me that there was a bit of a problem in that it was very heavily biased towards certain kinds of music, like playing recorder, playing guitar, following a score, learning to read and write music. The priority was to get people to the point of reading and writing music - and that's fair enough, that's a great thing to do - but what was obvious to me was it was actually just alienating a lot of kids. They don't want to work that way.

So instead of music being this kind of joyful group activity that actually is quite restorative and healthy, music became this really horrible thing that people were just disengaging with. And the teachers understood this as well.

Rian: Music education really can be a bit toxic if you go into details. For instance, Georgina Born, the researcher and academic, was saying that music education is statistically sort of proven…

Mark: …I think she found that for example A-level music was shown to turn young women off pursuing careers in music.

Rian: Right, and a big part of music education is like ‘you have to learn how to play this before you can play it’. What's that about? Can't you just be like, ‘I'm going to make some sounds and explore it in that way’? But then it's about finding alternatives in a way that the participants really find exciting. I was speaking to a teacher recently who started introducing DJing as part of the GCSE exam, and they were saying loads more kids are getting through GCSEs now because they have this new thing.

Mark: We need to be careful because that isn't ‘let's erode the standards so that more kids can pass’. It's more ‘let's change the boundaries of what constitutes acceptable practice in the context of a GCSE so that more people can have a lifelong engagement with music’. That's what my prejudice is: that everyone should have music as part of their life, so that's what we try to do at the Electronic Music Club.

When we did our pop-up at Hope Works in January, there were two young guys and the teacher was like, ‘these two guys have just got to stand outside’. Normally these two guys find it overwhelming so they just stand outside, chill out a bit and wait for the bus home, but Rian went out and talked to them. I don't know what you said to them, Rian, but it ended up that you got them DJing. Since then they stuck at it and they’ve started DJing at events in the town centre. They just needed a way to be in the room that felt right for them. So that's what we try to do.

The Electronic Music Club pop-up at Hope Works

The Electronic Music Club pop-up at Hope WorksRian: When you set up music sessions that people can come to, you find that everyone is into some form of music. I don't think I've ever met somebody that actually doesn't like any form of music. So it’s about finding that door for each person and what's their way into it, and then how do you respond meaningfully to them that enables them to do it. I think that's probably a lot of the problem with education: it's like this broad generalised approach. How can you have this general objective thing that works for everyone?

Mark: Can I just jump in with an anecdote? Do you remember when we were doing the Electronic Music Club at Hope Works and we'd got all the synths that Signal Sounds had sent and also Finlay Shakespeare turned up with a bunch of stuff. We had this massive table - it must have been a four metres square - full of synthesisers, and all the kids sat around the perimeter and they were just all completely into it. I've never seen a room of kids concentrating so much. The teachers couldn't believe it. So then it got to lunchtime and I'd ordered loads of pizzas and doughnuts. And half the kids didn't leave the table. Half the kids carried on sitting around the synths and were like, ‘No, I want to carry on doing this. I'll have some food later’. A lot of these kids are hard to engage. So yeah, I'm totally evangelical about synthesisers. I think synthesisers should be prescribed on the NHS (the UK’s national health service).

Tom: You've obviously both performed in lots of different contexts, from clubs to art spaces. How does doing a workshop with young people compare to performing to an audience who are there to see you as an artist?

Rian: I remember around 2017, I’d just played in Berlin, in the Berghain basement - that was the biggest deal I could have imagined for me at that time, it was a properly amazing opportunity. Then literally the day after I flew back to Rotherham it was a town festival and I was doing maybe the second workshops I'd ever done. I got these kids to DJ and there wasn’t even really a stage, it was a table in a field, and there were about 40 kids coming in doing cartwheels and stuff and all going crazy and I just totally loved it. I was telling people it was even better than playing at Berghain.

Mark: Also when you're doing workshops, I think I learn so much more. It's not just about what the kids get out of it, but I learn so much more about what I'm doing, about music. I feel like I grow much more as an artist because of that kind of activity as opposed to just going on a stage and doing the 45 minutes of theatrical stuff. I mean, I love performing, but when you're performing, you just learn about performance - you learn about how to respond and read an audience and all that kind of stuff. I learned so much other stuff from being in a room with a bunch of people in a workshop context.

Electronic Music Club participants learning about DJing

Electronic Music Club participants learning about DJingTom: So what’s next for the Electronic Music Club?

Mark: Our priority now is to get a permanent home for it. What we want to do is establish a sort of radical electronic music community art space in the town centre. And I think we're getting there. We're working with some partners to redevelop some buildings. We've been given a derelict pub, which we're trying to find the money to renovate now. That'll be a great space if we get it together. But we're not working with rich property developers. It's just total breadcrumbs of funding and stuff and real grassroots sort of activity. It's hard to make things happen. I'm way out of my depth and comfort zone. Just trying to turn a derelict pub full of pigeons into a community art space is really difficult.

Rian: What’s really interesting is our connection with real grassroots local activities - being from that town, knowing communities, actually growing up there - but then having this more international artistic network and the opportunities in that. We're able to sort of connect those two things and it's quite unusual and everyone involved has been really into it. For instance, we had Lord Spikeheart come over from Uganda to do this screaming workshop, and before that RP Boo was doing footwork workshops in town - it’s just completely mind- blowing for me.

Tom: I guess music like that would normally be the preserve of people that read The Wire over here… so to present that to people that have never been exposed to anything like it before it must be really interesting.

Rian: I love it. And I think that's a real sort of drive for me. You get so inspired by music and it has such a big effect on you and then you get a bit ‘seen it all before’ and you go to gigs and no one's even bothered. They're all just on their phones. But when you do stuff like getting someone to DJ in a little youth club, you can just see their minds being blown, like the thing we did with Finlay at Hope Works.

Mark: We were using the club sound system, basically - this enormous and amazing sound system. Imagine those kids, they've got their hands on a synth, they're producing a really high quality sound at not dangerous levels, but substantial levels. The feeling that you get from turning a parameter on a synthesizer and hearing it really big… it's just completely intoxicating, I think, to do that.

Rian: Honestly, I think that would have changed my life if I’d done that. I actually think some of these things will be lifechanging. It sounds quite dramatic…

Mark: But I think for some kids it is. I just think it's really important to give kids alternatives to the mainstream. That’s what it's all about for me. It’s not about saying ‘this is superior’ or whatever, but just opening up different doors and seeing which doorways they choose to go through.

No Bounds is at various venues in Sheffield and Rotherham from 11-13 October. Find out more about Mark Fell, Rian Treanor and the Electronic Music Club.